So now that Stanley “Tookie” Williams is dead, let us take a moment and recognize how he turned his life around while incarcerated for his conviction of murdering a 7-11 clerk and a hotel owner, his wife and daughter.

So now that Stanley “Tookie” Williams is dead, let us take a moment and recognize how he turned his life around while incarcerated for his conviction of murdering a 7-11 clerk and a hotel owner, his wife and daughter.Yes, he was a vicious hoodlum in his youth. Yes, he most definitely deserved, at the very least, to spend the rest of his life in a cell. Yes, the friends and family members of his victims were entitled to see him die as the sentence passed after he was convicted by a jury of his peers was carried out.

But didn’t his good work count for something? And isn’t it a loss for us all that he will no longer be able to write, teach, and mentor other violent, aimless young men regarding the waste and death that inevitably follows when they choose a life of gangland violence?

As I sorted through my thoughts and feelings about what this story meant to me personally (and I can only imagine how those much more closely involved with Williams feel at this moment), one name came back to me over and over in my mind (another person I never knew, but only through someone else’s interpretation of him). Partly because of this person, a precedent exists for granting clemency to convicted murders and sparing the death sentence.

The name of that person is Robert Stroud. You can read more about Stroud from this link (I read the Wikipedia article, and it looks completely authentic).

As mentioned in the article, Stroud was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked Stroud’s girlfriend at the time, earning a conviction which led him from McNeil Island in Puget Sound to the federal pen in Leavenworth, Kansas. At Leavenworth, Stroud killed a prison guard in a cafeteria dispute, and after an invalidated trial, Stroud was tried again and sentenced to death (with intervention to make sure the sentence was carried out by the U.S. Supreme Court), which was scheduled to take place on April 23, 1920.

As mentioned in the article, Stroud was convicted of murdering a man who had attacked Stroud’s girlfriend at the time, earning a conviction which led him from McNeil Island in Puget Sound to the federal pen in Leavenworth, Kansas. At Leavenworth, Stroud killed a prison guard in a cafeteria dispute, and after an invalidated trial, Stroud was tried again and sentenced to death (with intervention to make sure the sentence was carried out by the U.S. Supreme Court), which was scheduled to take place on April 23, 1920.Stroud’s mother then appealed her son’s death sentence to the President, who at that time was Woodrow Wilson. However, I believe that, at this moment, Stroud benefited from a fateful bit of good luck. Wilson had been thoroughly incapacitated by a stroke in October 1919, and for all intents and purposes, Wilson’s ambitious second wife Edith Bolling Galt Wilson was running the country (a fact hidden from just about everyone somehow, including Vice President Thomas Marshall). I believe that Stroud benefited from the fact that his mother could appeal more directly to the First Lady instead of the President (I have not been able to determine if Gault had had children prior to marrying Wilson – I think she did, but I’m not sure).

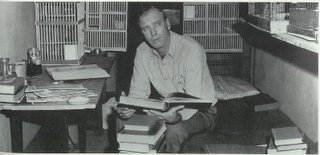

The remainder of the Wikipedia article discusses Stroud’s accomplishments after his death sentence pardon in the area of avian science, including authoring the books Diseases of Canaries and Stroud’s Digest on the Diseases of Birds. This was all captured pretty accurately I thought in John Frankenheimer’s landmark 1962 film about Stroud called “Birdman of Alcatraz” starring Burt Lancaster (though, ironically, Stroud studied the birds in Kansas and not Alcatraz). There were some Hollywood touches to be sure in the film – Stroud/Lancaster matures into a wise, genial old man by the time he leaves for the Medical Facility for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri, where he died on November 21, 1963, ignoring Stroud’s violent mood swings depicted earlier that remained in his old age, and Stroud was also a generally unkempt individual, which I guess should be expected when you’re housing a bunch of birds, and that was glossed over – but there was much more in the movie that was realistic and thought provoking (in his day, Lancaster definitely championed what we would consider to be liberal causes, and probably would have been leading the fight to save Williams).

As I said at the outset, though, I think this is an occasion to pause and reflect on the good work of prisoners such as both “Tookie” Williams and Robert Stroud as part of their incarceration. It is easy to feel that that is a small payback for the violent acts that put them behind bars, and that’s a good point. However, that makes their contributions no less significant.

And how many more prisoners will follow in Williams’ footsteps if they believe that their lives will not be spared if they do so?

Update: In this post, I didn't read Michael Smerconish refuting anything pointed out here by The Bulldog Manifesto several days earlier. What I did read was some truly disingenuous association by Smerconish between "Tookie" Williams and Mumia Abu-Jamal. Are we to judge the merits of whether a man lives or dies based on the individuals he cites in a book dedication?

No comments:

Post a Comment