I read about how our gal Condi Rice is telling us to make nice with Libya and its High Exalted Leader Moammar Qaddafi now since we’re such good friends, apparently.

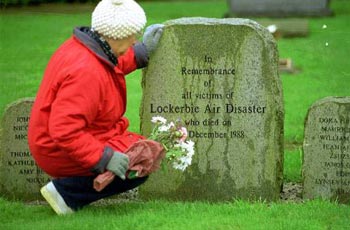

I read about how our gal Condi Rice is telling us to make nice with Libya and its High Exalted Leader Moammar Qaddafi now since we’re such good friends, apparently.To be fair, I should point out that Libya has worked hard to make reparations to the families of the victims of the Pan Am Flight 107 bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1987 (which is the very least they could do since they accepted blame for that horrible attack).

However, we should not assume it is now just peachy for Americans to travel there. As this State Department advisory tells us:

Americans who apply for Libyan visas are experiencing significant delays, often waiting several weeks or months before their applications are approved. It is recommended that Americans obtain individual Libyan visas prior to travel, rather than group visas. Americans who expected to enter on group tour visas or individual airport visas arranged by Libyan sponsors have frequently been denied entry at the air and sea ports and have been forced to turn back at the airport or remain onboard ship at the port. Because of lengthier administrative processing for American visa applicants, many cruise ship operators no longer include Americans on their group tour applications, creating a great last-minute disappointment for those American passengers who expected to visit Libyan archeological sites.This (along with the fact that Lybian drivers must be the most dangerous in the world) was confirmed by Andrew Solomon writing in The New Yorker in an issue that appeared last week, in which he described bureaucratic ineptitude and arrogance typical of what is basically a tribal nation trying to keep up with other industrialized countries.

“In some areas—notably with respect to civil liberties and economic restructuring—the rate of change is glacial.... In other areas, change has occurred with startling speed.” Foreign goods are available, satellite TV is prevalent, and Internet cafés are crowded. One senior official said, “A year ago, it was a sin to mention the World Trade Organization. Now we want to become a member.” Yet, Solomon observes, “Few Libyans are inclined to test what civil liberties they may have.... The atmosphere is late Soviet: forbidding, secretive, careful, albeit not generally lethal.” And Qaddafi has by no means become a beloved figure. Solomon writes, “It is the most arresting of the country’s many paradoxes: Libyans who hate the regime but love Libya cannot tell where one ends and the other begins.”There was also a photo in Solomon’s fine article of a HUGE poster the equivalent of a billboard ad we would see near a highway with Qaddafi’s face on it (and by the way, why is it that world news organizations could never get the spelling of his last name right?), and these posters must appear throughout Libya.

Qaddafi’s second oldest son and possible successor, Seif el-Islam al-Qaddafi, “is to be the face of reform,” Solomon writes, and, he adds, “The relationship between father and son is a topic of constant speculation.” While Libyans, who are afraid to refer to Qaddafi by name, call him the Leader, they refer to Seif, who is one of eight children, as the Principal, or the Son. Seif is pursuing a doctorate in political philosophy at the London School of Economics, and, Solomon notes, “he founded the Qaddafi International Foundation for Charity Associations, which fights torture at home and abroad and works to promote human rights. He appears to be committed to high principles, even though real democratic change might put him out of the political picture.”

This article, though, explains why the U.S. would want to restore relations with Libya (attempts at normalizing relations began late in the second term of the Clinton Administration).

Many Western leaders had written off Qadhafi as unfathomable and mercurial, and for that reason, had been reluctant to engage in any dialogue. Their distaste for the Libyan leadership, however, seems to have obscured the many ways in which Libya was a problem that lent itself to resolution.This is all good news, and if I were actually inclined to give Dubya credit for anything (which I’m not), it would be for this, but only slightly. However, as Prime Minister Shukri Ghanem puts it:

The benefits of the Libyan turn have been massive. Not only has the United States won important cooperation from the Libyans on counterterrorism, eliminated uncertainty over proliferation in North Africa, and helped secure justice for the families of victims of Libyan-sponsored terrorist acts, but the discovery and subsequent disruption of proliferation networks that had been supplying the Libyan government has had ripple effects beyond North Africa to the Persian Gulf, Africa, and Asia. All together, the benefits of U.S. engagement with the Libyans have exceeded many of the expectations not only of skeptics but also of advocates. From the Libyan side, most of the benefits have come indirectly—not from the U.S. government but from corporations seeking to enter the Libyan market. Libya has shed its international pariah status, and Tripoli in five years is unlikely to bear much resemblance to its current state.

“We would like a relationship, yes, but we do not want to get into bed with an elephant…deep down, the Libyans think the U.S. will not be satisfied with anything short of regime change.... And, deep down, the Americans think that, if they normalize relations, Qaddafi will blow something up and make them look like fools.”I don’t think Michael Corleone could have put it any better than that.

And by the way, Steve Almond doesn't trust Madame Secretary either.

Update 8/21/09: Interesting behavior by one of our "allies" (here)...

No comments:

Post a Comment