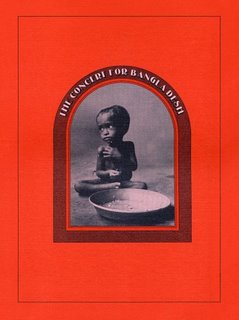

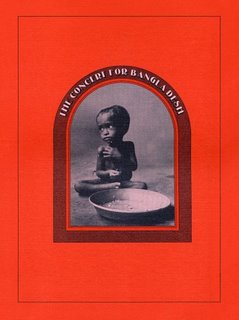

It has been my great pleasure over the last few days to view and listen to the brand new DVD production of

The Concert For Bangladesh, the benefit concert produced, arranged, and made to happen on just about every level by George Harrison in 1971 (the non-limited deluxe edition with Harrison on the cover).

This link takes you to the concert website which provides historical background on the conflict between East and West Pakistan at that time that ultimately led to the trail of suffering for the Pakistani refugees attempting to settle in Bangladesh, only to be thwarted by famine, poverty, and disease. There are some obvious parallels, I believe, to the crisis for which Harrison provided aid and the human misery currently holding sway in Northern Uganda and the Darfur region of the Sudan.

On August 1, 1971, there were actually two sets performed by the musicians, one in the afternoon and one in the evening. I purchased the three-LP vinyl set many years ago, and even since then, I have never been able to determine whether the afternoon or evening sets were recorded for the three-LP collection and film, or if it was some combination of the two. It’s a small matter, actually, because the terrific quality of the performances makes it a moot point. As is pointed out in a recently-filmed interview segment with some of the remaining performers, the “buzz” generated by the audience from the afternoon show added to the excitement of the evening show.

The DVD begins with an excerpt of a news conference George Harrison and Ravi Shankar gave announcing and promoting the concert, and then leads into the show with Harrison’s stage introduction to the Indian musicians and their performance. At first, I couldn’t understand why Ravi Shankar asked everyone not to smoke, until I realized as the show progressed that the non-Indian musicians smoked like chimneys, so to speak.

Harrison, in the introduction, asked people to realize that the Indian music (“Bangla Dhun”) was more “serious,” but the musicians certainly seemed to enjoy themselves as they played, particularly Shankar on the sitar and Usted Ali Akbar Khan on the sarod during the “Gat,” or quicker-paced part (the “jam,” if you will). Shankar and Khan seemed to play their mini-solos off each other like seasoned session players.

When the Indian musicians left, Harrison returned with the “all-star” band and led off with three numbers from “All Things Must Pass” (for my money, the best of the Beatle solo albums). “Wah Wah,” provided a rousing start, with the more contemplative “My Sweet Lord,” and a by-the-numbers-but-satisfying version of “Awaiting On You All.” The first band performer to be showcased was Billy Preston, which was appropriate partly because of his contribution to the Beatles, and his soulful reading of “That’s The Way God Planned It,” included a spirited, unrehearsed dance that whipped up the crowd (which caused Phil Spector, who engineered the sound, to ask repeatedly in a panic, “Where is he? Where is he?” when he couldn’t hear Preston at the mike, something noted on one of the four documentaries on the Special Features Disk #2).

Ringo Starr then performed “It Don’t Come Easy” (his synchronization with fellow drummer Jim Keltner throughout the performance was very nearly perfect), and Harrison performed “Beware of Darkness” with an unexpected twist of letting Leon Russell sing one of the verses. After the band introduction (where Harrison notes humorously that he “forgot Billy Preston”), Harrison performed “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” trading off with Eric Clapton on a couple of solos (I thought it was interesting, given that I am basically a non-musician, to watch Clapton cue Harrison, who subsequently cued the rest of the band, when it was time for Clapton to finish his solo and end the song).

It probably goes without saying that there are a whole bunch of stories behind this production, but probably the most visible one was that of Clapton. In one of the special features documentaries, Harrison noted that, after Clapton agreed to perform, telexes were sent back and forth to London to get a confirmation that Clapton would fly over for the performance, but nothing could be confirmed. Harrison contacted Jesse Ed Davis to play lead guitar in case Clapton couldn’t make it, though Clapton eventually showed up after missing the “sound check.” Of course, Clapton being who he is, he stepped onstage just about without the benefit of a rehearsal and played very well. I though it was also interesting to hear Clapton mention that he was playing his great solos on “the wrong guitar,” having left his Fender Stratocaster in London.

To his credit, Clapton was also very candid in one of the documentaries about his personal problems during that time, noting euphemistically that he had been in “semi-retirement” for about two and a half years, though also noting that hard drugs had become a big problem in music towards the end of the 60s, particularly heroin, implying his own use. He and others on the documentaries felt that part of the great appeal of the concert was that it was a revival of the music of the ‘60s without all of the excesses (I cannot recall who noted that multi-act concerts had gotten a black eye after

Altamont, and that is why there had not been any for some time, but fortunately, the Concert for Bangladesh changed that).

The next featured performer was Leon Russell, who ripped through a medley of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” by the Rolling Stones and “Youngblood” by Lieber/Stoller and The Coasters. Others would note after the concert that the highlight of the show was the performance by Bob Dylan that would soon follow, and he was terrific, but for me, Russell’s set was positively electric. He was about to explode in popularity as a solo performer, and his revivalist sort of gospel-influenced rock with the shouts back and forth to the backup singers got the crowd back into the show once again, helped considerably by a couple of blazing guitar solos from Don Preston (with Harrison nearly missing his cue a couple of times on the chorus). Harrison then performed an acoustic version of “Here Comes The Sun,” with Pete Ham of

Badfinger, one of the many supporting musicians and singers.

In one of the documentaries, Harrison noted that, when Dylan first saw the stage at Madison Square Garden and watched everyone setting up during the sound check, Dylan said, “Hey, this isn’t my thing,” and Harrison said, “It isn’t mine either, and I’ve never fronted a band or anything like that, but at least you have.” Because of Dylan’s hesitation, Harrison noted “Bob ?” on the song list after “Here Comes The Sun,” and very nearly towards the beginning of Dylan’s performance, it wasn’t known if he would even show up that afternoon. However, show up he did, fortunately. Ringo Starr noted later that, since no one knew exactly what he would be performing, everyone just “went with it, and we played a 4/4 time throughout for his afternoon set,” but when the evening came along and Dylan started, Starr’s reaction was, “Oh, now we’re playing a waltz.”

The first song Dylan performed was “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” followed by “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry.” On the Dylan set, Harrison played a slide guitar accompanied by Ringo on tambourine, which I thought was interesting. You can’t tell that from the film, and in fact a lot of the camerawork was a constant source of irritation to me, until I watched the “Making Of The Movie” featurette and realized what an enormous technical challenge Saul Swimmer faced in making the film. Now, we take for granted the precise framing of shots when filming music performances, along with the sweeping camera movement and synchronized editing with the music, but in terms of technological innovation, this concert took place in the stone age. The fact that that is reflected somewhat in the camerawork, which seems to constantly be a step behind the performance, does not convey all of the hard work that went into filming this show (the only moment of note in that department was the split screen of Shankar and Khan finishing their performance of “Bangla Dhun,” which was actually typical for many films during that time).

Dylan then expertly brought “Blowin’ In The Wind,” and “Just Like A Woman” back once more before concluding. However, one mystery to me regarding his set is the absence of “Mr. Tambourine Man” on the DVD. I checked some message boards, and some people said that the film ran out during the song, and that is why it appears on the original vinyl LP and the CD but not the DVD. That makes sense – one of the problems Swimmer noted was that no one knew at the time to “stagger” the filming of the concert, so on occasion, the cameras ran out of film at the same time. However, I also read a post that said the performance shows up on a version of the DVD for European distribution. I may never know the answer conclusively, but I don’t think that detracts from the DVD. Besides, a previously unseen version of “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” played during the evening set appears as a special feature, and it is truly a gem, more than making up for “Mr. Tambourine Man” as far as I’m concerned (other special features include “If Not For You,” with Harrison trying hard to provide on harmony vocal for Dylan on the duet, and a raw version of “Come On In My Kitchen,” a Robert Johnson blues standard brought to life in a rollicking fashion by Harrison, Clapton, and Russell).

Harrison wrapped up the show with “Something,” messing up the words and having a bit of a laugh over it. This was in keeping with all of the good spirit throughout the show, which seemed to almost reverberate back and forth between the audience and the musicians. As a bit of trivia, I thought it was interesting to note that Harrison was ostensibly singing about

Pattie Boyd, his wife at the time, while he played the tune with Clapton, who would begin a relationship with Boyd after she divorced from Harrison in 1977, marrying Clapton in 1979 until their divorce in 1989 (yielding the songs, “Layla,” and “Wonderful Tonight, by Clapton, as well as Clapton’s searing cover of Billy Myles’ “Have You Ever Loved A Woman,” about her, making Boyd a true legend in rock music).

As an encore, all the musicians returned to perform “Bangla Desh.” As they furiously ripped through the rousing finale, it seemed as if Phil Spector’s attempt to recreate a live “wall of sound” with the almost ridiculously overcrowded stage had finally succeeded.

The main documentary on the Special Features disk #2 presents remembrances from Ringo Starr, bassist Klaus Voorman, Billy Preston, Jann Wenner of “Rolling Stone” magazine, Leon Russell, UN General Secretary Kofi Annan and many others interspersed with heaping doses of the great music (Harrison noted that John Lennon told him to use “the power of the Beatles” to get the musicians and otherwise make the concert happen). One documentary about the making of the film contains interviews from sound engineers Norm Kinney and Steve Mitchell where they describe “having to cram 44 audio tracks into 16,” and also with Swimmer who describes having to “blow up” the filmed shots of the performers frame by frame to 70 MM to accommodate the sound.

The film documentary also includes a brief interview for a local news station with concert goers camping out at MSG in advance to buy tickets; the news reporter conducting the interview is a newbie journo wearing a wide-lapelled powder blue polyester sports jacket named Geraldo Rivera (not yet looking inside Al Capone’s vault). The album documentary shows Harrison discussing some of the business problems related to the concert, primarily the fact that the distribution company of Capitol/EMI, the label upon which the concert was recorded, held up release of the record over money. That was resolved eventually, of course, and also included in the documentary is a film clip of Johnny Mathis presenting the 1972 Best Grammy award to Ringo Starr for the album, which beat out “American Pie,” by Don McLean and “Moods” by Neil Diamond.

Harrison noted that the concert raised about $250,000 which went to UNICEF primarily for oral re-hydration solution to treat the cholera from which the refugees were suffering. Others interviewed recently said that the concert helped people to feel “a renewed sense of activism,” with Clapton saying that this was a time “when we could be proud of being musicians…we weren’t just thinking of ourselves for five minutes.” Shankar, quite simply, called the concert “a miracle.”

I thought the quality of the video on the DVD was quite good given the primitive master from which it was copied, and I listened to the concert in either of the two Dolby options, and the clarity of the sound was wonderful. The DVD can also be viewed with English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese subtitles.

I am proud to give my most enthusiastic recommendation to this new DVD release. If you care about the music of this period to any degree whatsoever, buy this set.